The Clockwork Heist

A flash fiction about dead gods, small sins, and the doors we never opened

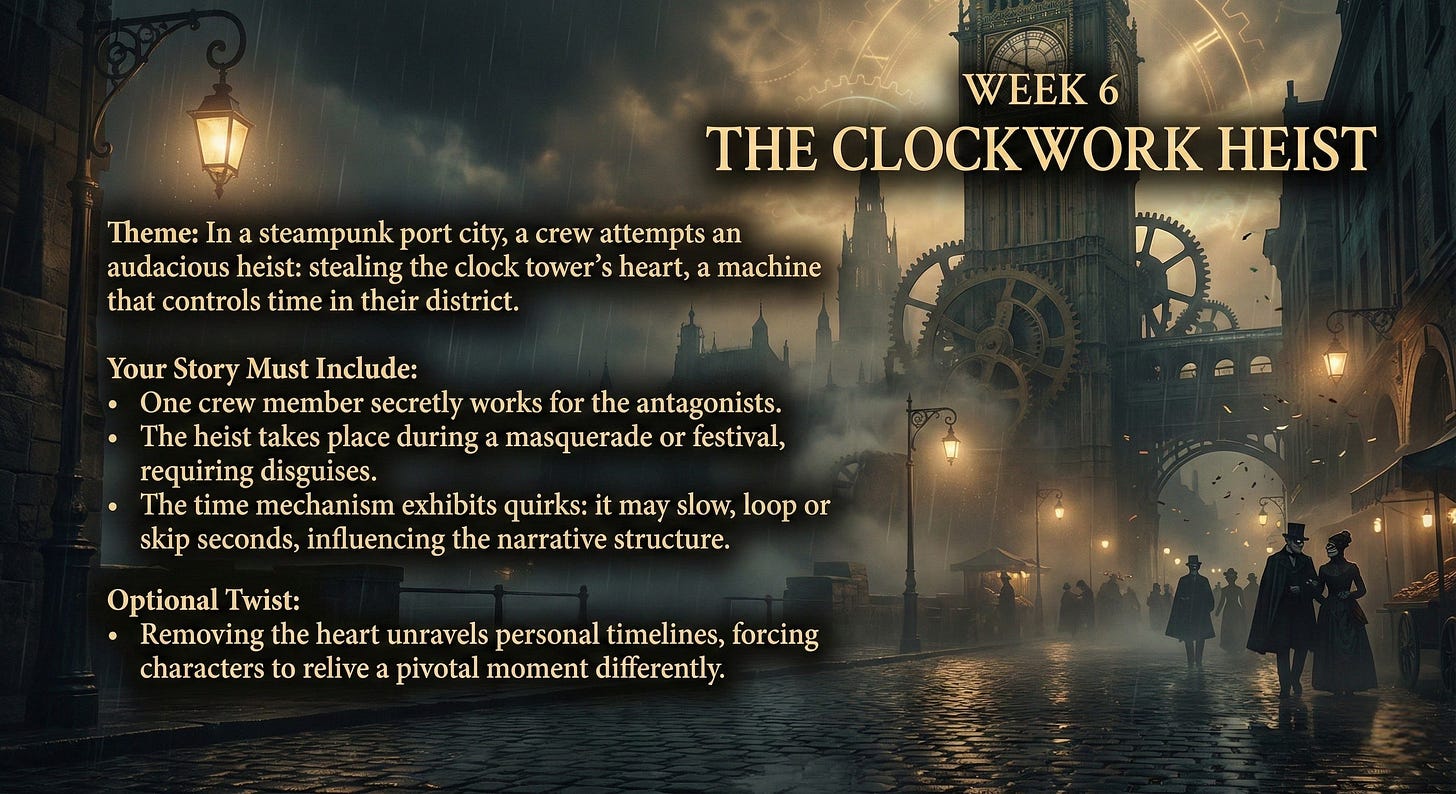

This is my entry for A.M. Blackmere’s Week 6 writing prompt. The challenge: a steampunk heist, a clockwork heart, time that loops.

I don’t usually write steampunk. My comfort zone is somewhere between Mediterranean Gothic and quiet domestic horror—dead gods, yes, but not brass gears and gaslight. So this was fun: an excuse to step outside my usual territory and see what followed.

Here’s my piece.

The casing had no seams.

I’d been working it for three hours, goggles fogged with my own breath, the brass surface throwing back gaslight in patterns that hurt to follow. Senna had gone quiet an hour ago. Vek stood by the door, watching. The gears of the tower groaned somewhere below us, teeth the size of carriages grinding through the night.

No screws. No welds. No joints.

The surface folded into itself like a puzzle box designed by someone who hated the solver. Every time I thought I’d found an edge, it slipped away, became another face, another angle that shouldn’t exist. My torch hissed against metal that wouldn’t mark. The heat dispersed wrong, spreading through the brass like the whole thing was one solid piece. One living piece.

“Can you open it?” Vek’s voice. Flat.

I didn’t answer. I’d opened cathedral vaults in Meridian. The bone-safes of the Surgeons’ Guild. A lockbox that had been sunk in the harbor for sixty years.

This was different.

The tower shuddered. Steam vented from pipes along the walls, hissing through copper arteries thick as my arm. The pressure gauges beside the door twitched into red, then back. Somewhere, a valve screamed.

I found it by accident. Not a seam—a suggestion. A place where the metal remembered being two pieces. I worked the torch along it, slow, the flame reflecting in my goggles until I couldn’t tell what was fire and what was brass.

The casing opened like a wound.

The smell hit first. Wet copper and something sweeter underneath, the kind you learn to recognize in basements where debts get settled. Then: cheap flowers going brown in stale water. A smell with no place here, no reason.

I expected clockwork.

Tubes. Glass and rubber, threaded through tissue the color of old wax. Pumping something too thick for blood through vessels that pulsed with their own rhythm. Steam rose where the liquid met air. And at the center, the size of a man’s torso, it beat.

Thud.

The surface was slick. Not oil—fever-sweat. The film on skin that’s been sick too long. Pale green, the color of hospital corridors, of doors that need repainting.

I should have stepped back. Forty thousand marks and a boat east. Clean numbers.

Thud.

I touched it.

The room is smaller than I remember.

Mother’s room. The hospice on Verne Street, the one with the cracked window they never fixed. I’m standing at the door. Paint peeling in the corner, same pale green. I have flowers—white, cheap, already wilting.

I don’t go in.

I watch myself turn.

Thud.

The room is smaller.

The flowers wet in my palm. Stems soft.

She’s thinner than I knew. Her hand on the blanket, fingers curled around nothing. Waiting.

I don’t go in.

Thud.

She’s turned toward the door. She heard my footsteps.

She’s smiling. That smile she had when she thought something good was about to happen.

I don’t go in.

I never went in.

She died eleven days later.

Thud.

Thud.

Thud.

I was kneeling. I didn’t remember falling.

The heart still pulsed under my palms. My hands wouldn’t move. I told them to move and they stayed, fingers curved against the sick-warm tissue like they’d grown there. My tongue was bleeding where I’d bitten through, and the taste mixed with the smell of flowers, copper, rot.

The room. The door. The smile.

The room. The door.

The room.

Vek was talking. I heard him from very far away.

“—can you hear me?”

The flowers. The wet stems. Eleven days.

“He’s gone.” Senna’s voice. Scared. “Vek, his eyes—”

“Get out.”

“What?”

“Get out. Take the boat. Tell them he touched it and it killed him.”

Footsteps. Running. The tower groaned and I felt it through my knees, through the floor, through the heart that kept beating against my palms in a rhythm I’d heard before, a rhythm like footsteps walking away, walking away, walking—

Vek knelt beside me. I saw him in pieces. The mask from the festival still hanging at his belt—a woman’s face, someone’s mother. His hands steady. A knife, short-bladed, meant for cutting.

“The church sends its gratitude,” he said. “You opened what no one else could.”

He reached past me. Toward the tubes.

I tried to speak. My mouth made a shape that might have been don’t or might have been please or might have been nothing at all.

“This is mercy,” Vek said. “The world has been numb for three hundred years. No consequence. No weight.” He looked at me, at my hands frozen on the heart.

“Murderers already carry what they did. They never forgot. But the rest of us? The small things we told ourselves didn’t matter?”

His blade touched the first tube. Glass. Rubber. Something that pulsed.

“Now we all pay.”

Thud.

The room.

Thu—

I don’t know how long I knelt there after the beating stopped.

The tower was silent. No steam. No grinding gears. The pressure gauges read zero.

Somewhere below, in the streets of the district, in the houses and the hospitals and the rooms with pale green doors, three hundred years of numb forgetting came undone.

My hands were still on the heart.

It was cold now.

I was still holding the flowers.

Postscriptum:

If you’re not already following A.M. Blackmere’s Substack, you should. These weekly prompts are a gift—a reason to write something new and a community to share it with.

As for the story: I wanted to take the genre somewhere darker. What if the clockwork was just a shell? What if underneath, something older had been keeping the world numb for three hundred years—not to protect us, but to let us forget? And what if the worst thing you’ve ever done isn’t the thing you remember, but the small thing you told yourself didn’t matter?

Underground Atlanta had fallen on hard times. A few rapes and a couple of gun murders were enough to drive upstanding suburban citizens away. One by one the restaurants and the toyrist trap shops closed to escape the lack of business from moneyed visitors and shabby thieves.

What was left were the braver homeless and a criminal element that moved into the shops and restaurants.

The heart of Atlanta had become infested with the mosquitoes and roaches of society's low down.

A clash between the homeless and robbers was inevitable.

Who was going to rule the Underground?

A mild earthquake shook ATLANTA one day and time seemed to change after that. Some say it was 3-1 Atlas messing with the polar vortex and others say it was the influence of God helping the homeless over the bad dogs of society.

But days after the criminals had pushed the homeless out, a fungal illness froma new Crack in the ground overtook the lungs of the robbers. They stopped breathing and all of them died. The homeless who had been outside for many years and had built up an immunity to most floating microbes so, with renewed purpose, they took over the Underground and made it a welcoming place for all who had no home

Thank you A. M.